I'm a sucker for traditional architecture. My wife and I fell in love with a historic Tudor Revival fixer upper in her hometown and moved in a few years ago. Two summers ago we spent our anniversary in Akron, Ohio just so we could tour Stan Hywet, one of the most celebrated historic homes in the United States. Last summer I carved an authentic seventeenth-century English strapwork pattern into an oak ceiling beam in my kitchen. For fun.

As a Reformation-minded theologian, however, I'm also highly sensitive to legalism in all its forms. (Legalism means binding anyone's conscience to anything other than God's revealed word.) Legalism is relatively easy to spot when whatever someone is being legalistic about isn’t inherently a moral issue. If I were to question your standing as a Christian before God based on whether or not you follow Mosaic dietary restrictions or mix different fabrics in your clothes, you would be right to question my grasp of the good news of Jesus Christ as “the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Romans 10:4). Those laws were commanded by God for a time to drive home the necessity of obedient devotion and to point out our need for Jesus. Eating shellfish or weaving spandex into your cotton socks isn’t inherently wrong for Christians. This is what God reveals in a vision to Peter, a faithful Jew, right before sending him home to eat with Cornelius, a Gentile: “What God has made clean, do not call common” (Acts 10:15). Adding our own attempts at law-keeping to our righteousness before God in Christ, Paul says, nullifies God’s grace (Galatians 2:21).

Legalism that rests on a faulty understanding of God’s word is sometimes tricky to spot. Legalism is a lot more obvious when I stand in judgment over others based on mere personal opinion. I might look down on you if the car you drive is too nice (or not nice enough) or I might grumble if my church’s coffee isn’t good enough to honor God (or maybe, by serving good coffee, I suspect my church of drifting down the slippery slope of cultural compromise). I hope most of us know such self-righteous judgmentalism about personal preferences is deeply destructive.

But what about things that don’t belong at either extreme of the legalism spectrum—things that are neither twisting Scripture nor nursing pet peeves?

Church architecture isn’t anywhere close to being one of the most important things in Christianity, obviously, but it does matter. It’s not merely arbitrary. It affects the life and worship of the church in all sorts of ways, visible and hidden. So does that mean the Bible condones a certain degree of architectural snobbery about our church buildings? Can I judge my brother’s spiritual maturity in relation to the height of his congregation’s steeple? Can I correlate my sister’s righteousness before God with her propensity for chairs versus pews? No. Binding other Christians’ consciences in any of those ways is still legalism. But here’s the thing: legalism often doesn’t feel like legalism when it happens in areas of life that matter—not just church architecture, but whether to drink or smoke, how to spend our money, or educate our kids. Who we vote for.

So in the rest of this essay, I want to look through the window of church architecture to get a clearer picture of what I think is one of the subtlest temptations to legalism: even mature Christians are prone to bind one another’s consciences when it comes to things that matter—particularly with things that have moral weight—yet which the Bible, often to our frustration, nevertheless leaves to the discretion of Christian freedom.

You don't have to go far to find examples of well-informed Christians lamenting the state of contemporary church architecture. I agree with those laments. Church architects used to build to magnify the glory of God and serve his people; now they often build to draw attention to bold visions or avant garde reimaginations of the sacred. Or, for those less artistically high-minded committees with stricter budgets, we build to maximize the efficiency of audio/visual systems, HVAC, and parking. Our churches are more likely to look like warehouses than houses of worship.

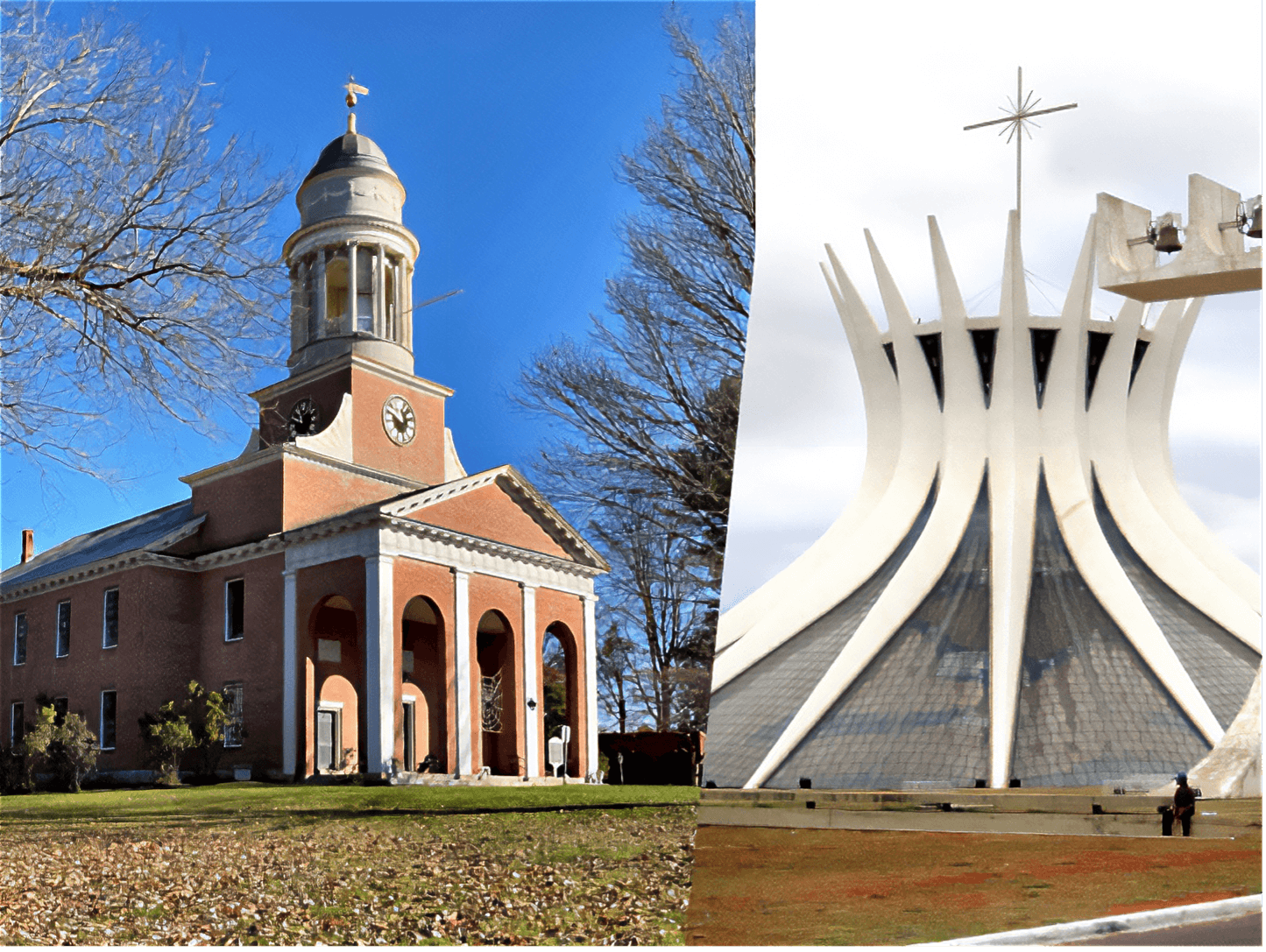

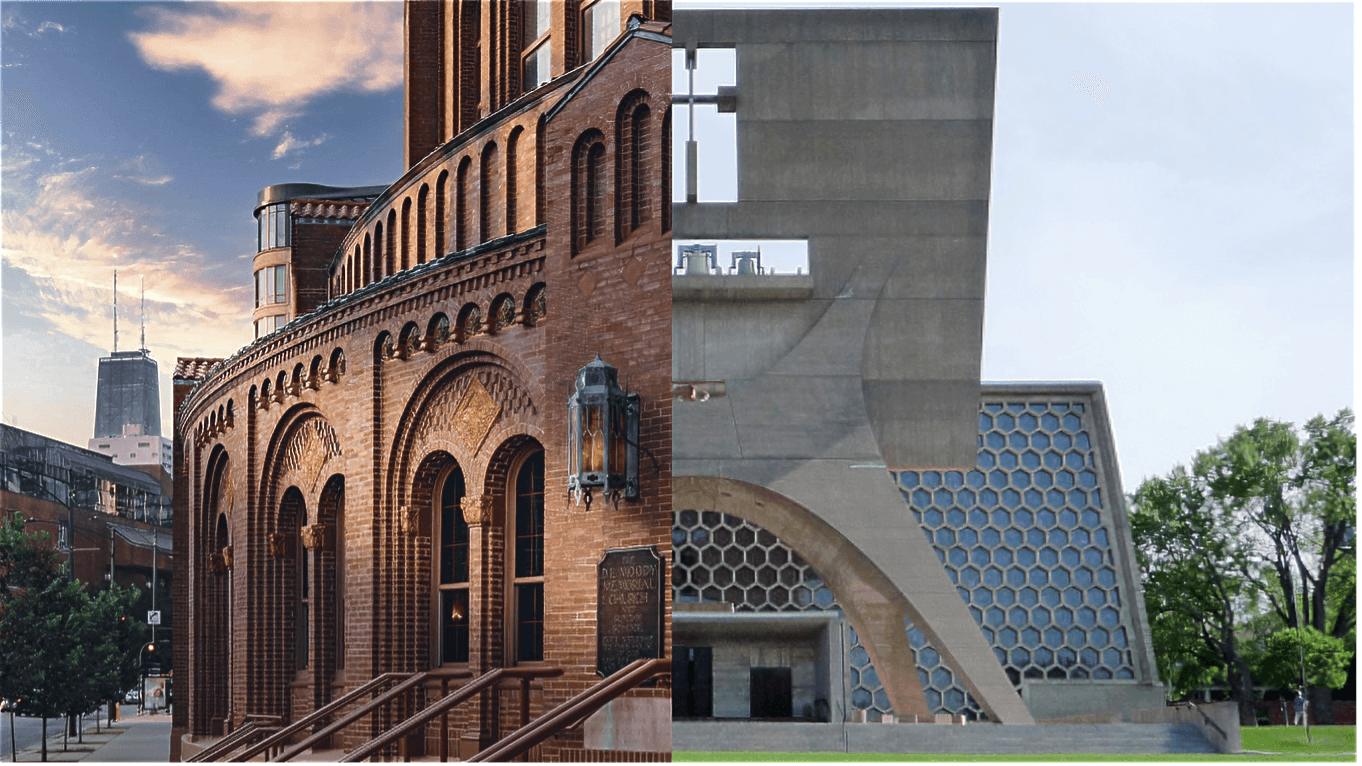

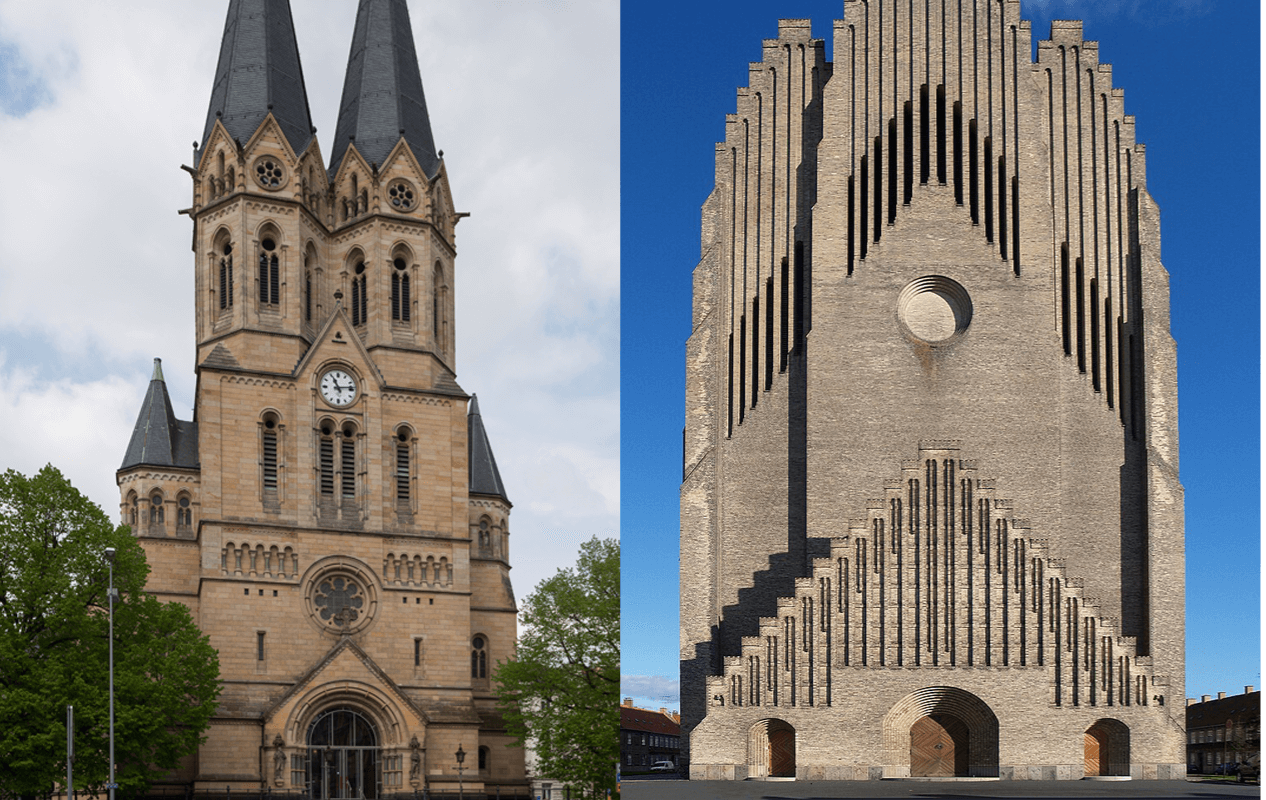

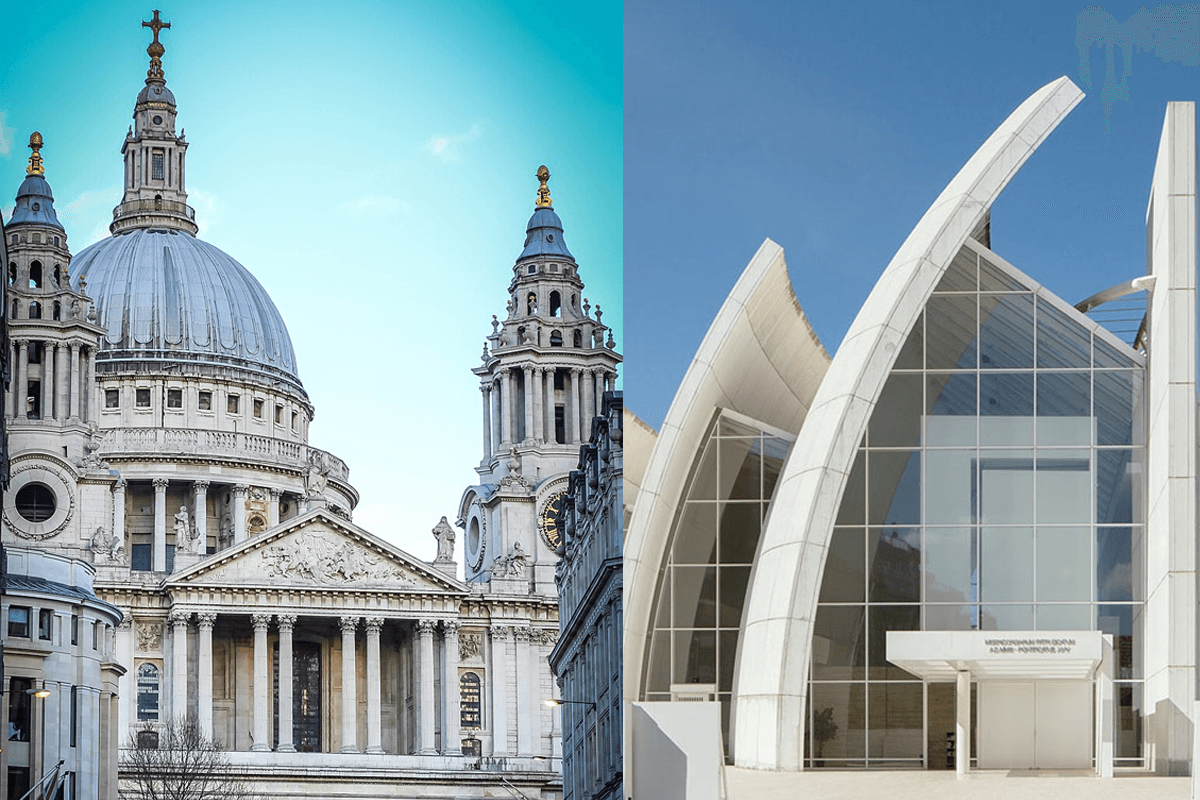

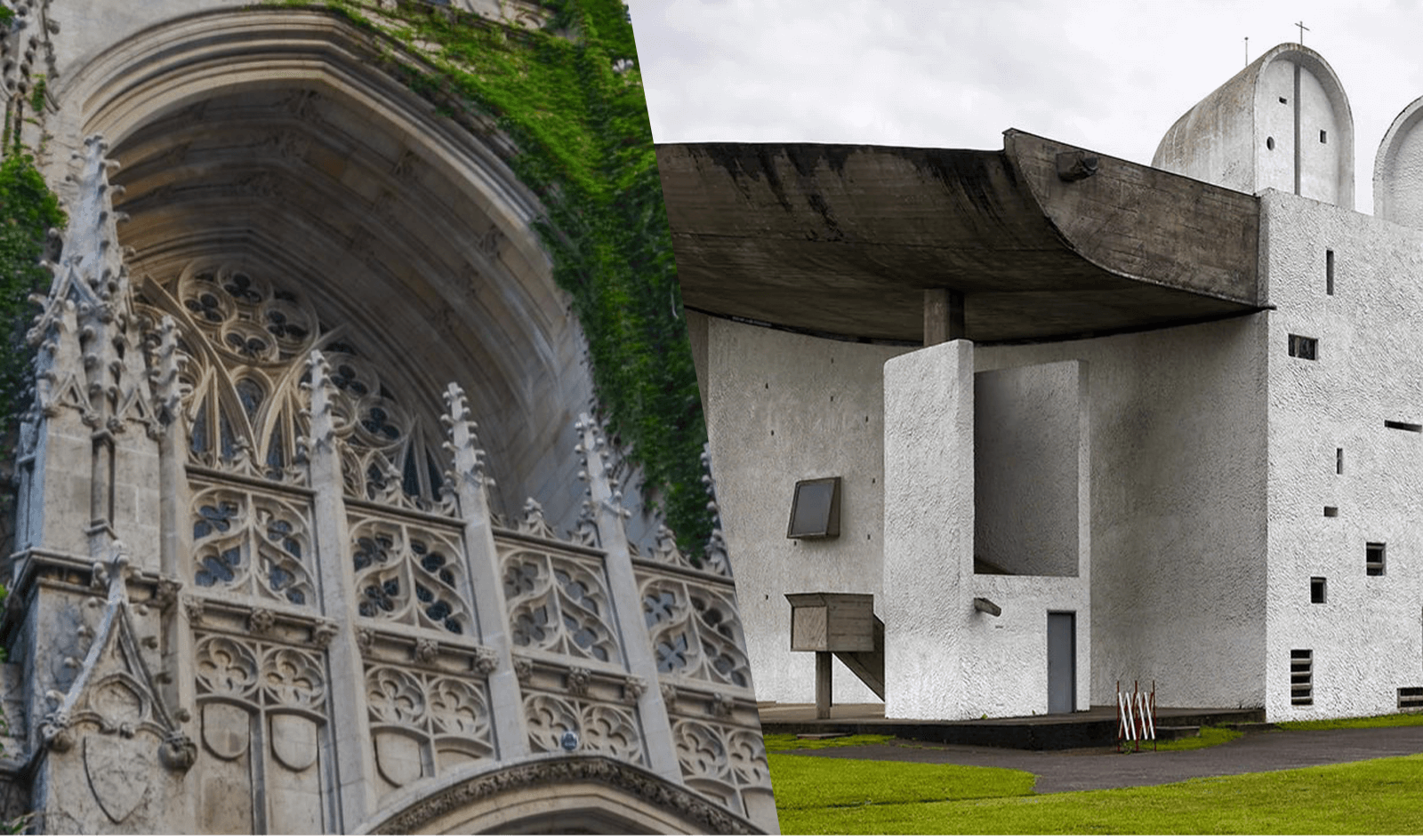

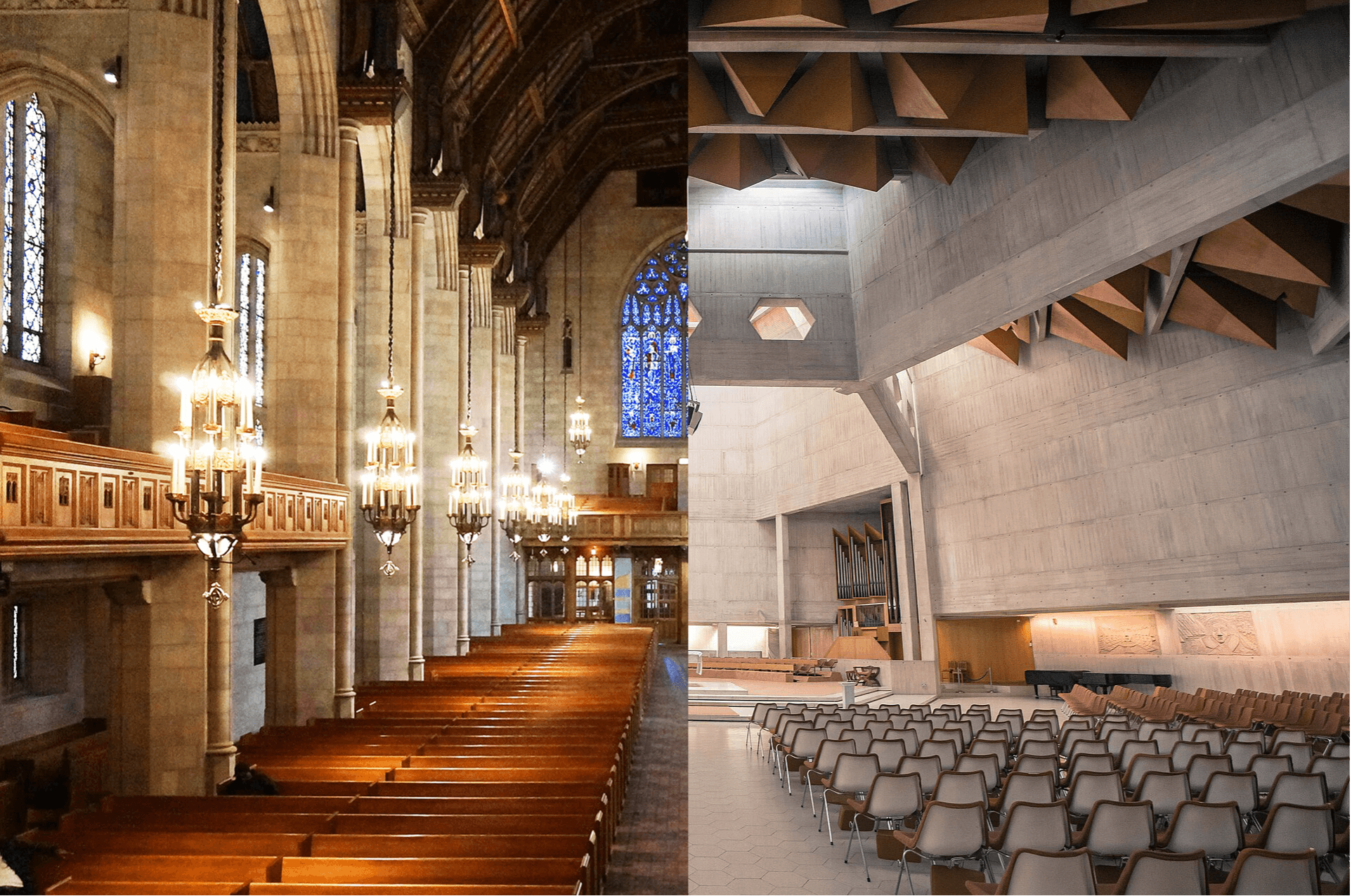

Whatever your personal preferences regarding traditional church architecture, it's almost universally celebrated as gorgeous. And not just among Roman Catholics or Eastern Orthodox or other traditions whose paradigm for worship is at odds with vital Reformational convictions. (All the traditional churches I've included in the split images in this essay were built by Protestants.) Consider, for example, the sheer thoughtfulness and love put into Hodges Chapel at Beeson Divinity School. It’s an architectural celebration of the heritage of the Reformation. In stark visual contrast, the designs of even the cleverest modern church structures are polarizing and often purposefully provocative.

It's not that Christians simply don't notice or care. Maybe the biggest irony of all this is that traditional and modern architecture usually cost about the same for the same level of quality. Neither is inherently more expensive. Rather, we assume traditional buildings are more expensive and difficult because we're comparing expensive traditional architecture to cheap contemporary architecture. So we usually back ourselves into a lose-lose situation. Do we choose cheap contemporary architecture that looks cheap, or splurge a little for expensive contemporary architecture that no one wants to look at? The result? Either way you go, everyone mistakes your church's new sanctuary for a Tesla dealership.

Sometimes all this really bothers me. We're embodied creatures! Our spaces matter! What we build reveals so much about what we value!

But you know what? The very next move I'm tempted to make is to take the leap from This matters to me and I think it should matter to you, to This is why I'm comparatively more enlightened and mature than you and my convictions should be elevated above yours. And that's when passionate personal conviction turns into judgmental, self-righteous legalism.

The truth is, we easily swing to one extreme or the other on meaningful issues like church architecture, largely based on whether we personally find them meaningful. At one extreme, some of us might treat church buildings like they don't matter at all. Who cares what our building looks like? Kids are starving in Africa while we debate woodwork. Swinging to the other extreme, some of us might judge others self-righteously, desiring to bind their consciences to convictions beyond God's word. I can't believe the deacons would suggest leasing the old community center downtown. All they care about is the bottom line.The truth is, church architecture really matters and we must refuse to bind one another's consciences over it.

This applies to everything for which God’s word allows freedom. It matters whether my son wants to be a plumber or a politician. Parenting and educational philosophies, technology use and digital habits, amount and frequency of alcohol and food consumption (short of drunkenness and gluttony)—all of these matter a lot and all of them are left to Christian wisdom in submission to the general principles of God’s word. I can't condemn you for making different choices with your freedom, or force you to conform your convictions to mine. Only God's word can make such demands.

I have specific and well-considered preferences or even strong convictions in each of these areas (architectural or otherwise), as I'm sure many of you do. How we educate our kids or what callings we pursue are big decisions. We can even say these choices carry lots of moral weight. Yet in each of them we as Christians enjoy freedom to act wisely in submission to the Spirit speaking in the inspired and authoritative Scriptures. If you’re not acting contrary to God’s explicit word, and especially if in important matters you’re humbly attending to the wisdom of the church and the counsel of pastors, elders, and godly, trusted friends, then you’re free. Go forward in the Lord’s favor.

So let's ask the opposite question with which we began: what kind of church architecture is worst? Any kind that swells my human pride and worldly security or which I wield as spiritual leverage against brothers and sisters in Christ.

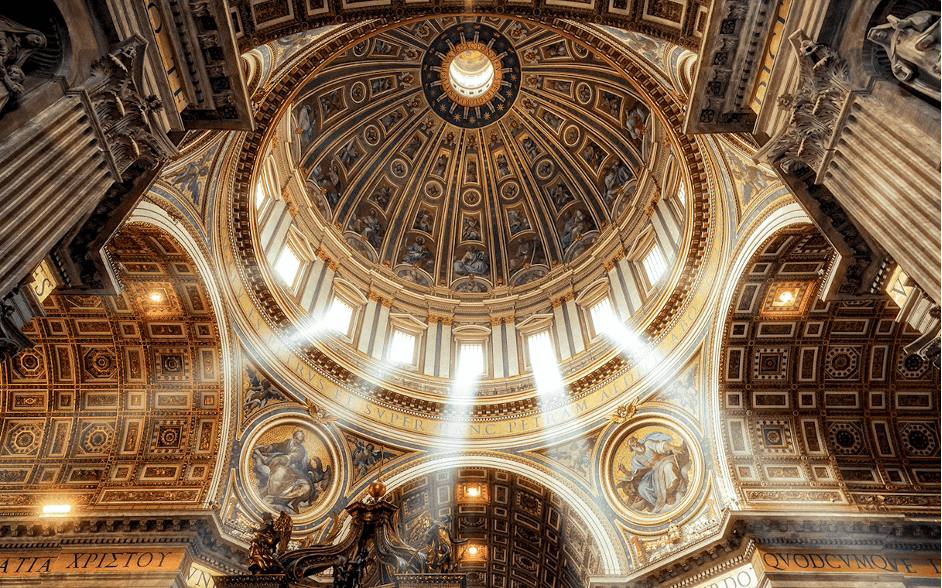

St. Peter's Basilica in Rome is one of the most awe-inspiring buildings I've ever seen with my own eyes. Many would say its grandeur is a fitting tribute to God’s surpassing glory. Others would call it a colossal waste of precious resources. Both positions have some justification, and neither position rises to the level of a gospel issue. You know what is a gospel issue with St. Peter’s? Its construction, beginning in the early sixteenth century, was paid for largely by the spiritually manipulative sale of indulgences to release souls from Purgatory, a fundraising scheme that motivated a young monk, Martin Luther, to publish his Ninety-Five Theses.

"Why does not the pope, whose wealth is today greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?" (Thesis 86)

Beauty and grandeur? Not wrong. Exploiting God’s people spiritually and financially when already as rich as Crassus, who was known as the richest man in Ancient Rome? Dead wrong.

Church architecture wasn’t a gospel issue back then, and it shouldn’t be for us today. Far better to bless your neighbor with grace and peace while surrounded by concrete and steel than to pile oak and marble on his back as he topples under the heavy load of law headlong into destruction. God is infinitely more glorified in an open cornfield where the good news is preached than in a palace where the word is silent.

We could argue all day about whether there’s such a thing as the objectively worst church architecture. But let’s go back to the original question about the very best church architecture. That's actually much more objective: it’s the church itself, the men and women made in God's image and redeemed by Jesus for his glory. These are the precious, living stones being built into a spiritual house fitting for the Lord. These stones have been covered with a righteousness infinitely more splendid than anything imagined by the boldest visionaries or crafted by the greatest artisans. They’re being beautified by the Spirit who invented beauty! And when this building is finally revealed in all its glory, no earthly structure will be worth comparing to it.

The best church architecture is the one “whose designer and builder is God” (Hebrews 11:10). And the best way to build this church is to preach the good news of salvation from manmade rules and the fulfillment of all God’s rules in Jesus the Righteous One who gives himself to us so we can give ourselves to one another.

In his famous little book, The Freedom of a Christian, Martin Luther explored a curious paradox about the Christian life lived between two seemingly contradictory truths:

A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none.

A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.

Only because Christ has set us free are we no longer slaves of sin. Only because we’re free in Christ can we devote ourselves freely to him and one another as slaves of righteousness.

Jesus is building a beautiful church set free from bondage under God’s law—so he has certainly set us free from bondage to your law or mine. And I build his beautiful church with him when I build you up in his love rather than tear you down by binding your conscience to mine. “For freedom Christ has set us free,” Paul says; “stand firm therefore, and do not submit again to a yoke of slavery.” (Galatians 5:1). Because “you have been set free from sin and have become slaves to righteousness” (Romans 6:18). No design, no material, no craft can compare with the beautiful fruits of God’s Spirit God bears in us by his life-giving word. “Against such things,” Paul assures us, “there is no law” (Galatians 5:23).