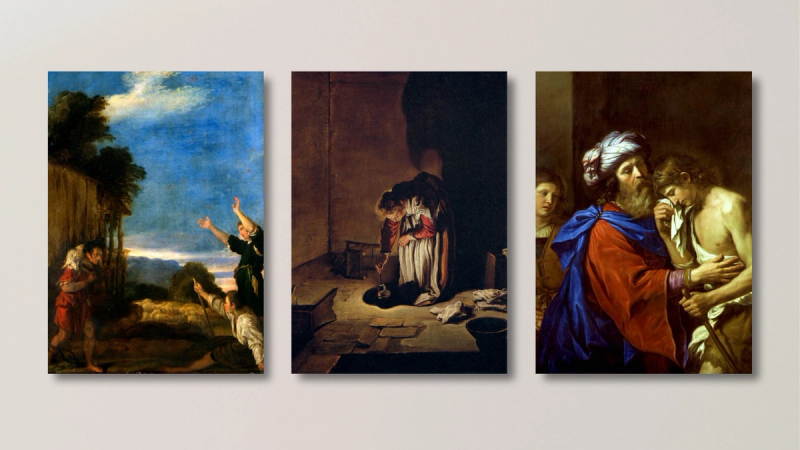

Luke 15 is one of the most compelling and memorable texts in Scripture. The images it conveys are certainly among the most timeless in church history, serving as ample sermon fodder for countless preachers and teachers for centuries. Who is the God of the Bible if he is not the shepherd who searches for the lost sheep? Who is he if he is not the father who scours the horizon, waiting for his wayward boy to return home? Even still, Luke 15 isn’t often treated as a three-part saga that must be kept intact in order to be understood. Instead, either through sermons or Bible studies, we are frequently shown what it means that Jesus is our Great Shepherd or what it means to truly repent as the prodigal son does. While each vignette in Luke 15 certainly stands powerfully on its own, the resonance of Jesus’s message, which showcases his heart and confronts our discomfort with grace, shines most brightly when the three are understood as a unified whole. Preaching Luke 15 in its fullest light means proclaiming it as a trilogy.

One Parable, Three Movements

Significantly, when Luke sets the scene, he refers to the entire discourse as “this parable” (Luke 15:3). Although there are three parts to it, each movement really tells one story. Like other great trilogies that are ingrained in our cultural lexicon—e.g., Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, or Toy Story—Jesus proceeds to tell a trilogy of stories that progressively unfurl the meaning and resonance of grace. “Grace,” of course, is the term that most clearly distinguishes the Christian faith from other avenues of religion. “Grace,” writes David Zahl, “is the most important, most urgent, and most radical contribution Christianity has to make to the life of the world—to your life and mine!” Unfortunately, as is often the case, grace is freighted with so many conditions and caveats that we end up losing its essence.

There’s a part of us that squirms and shudders at the notion of God’s merited favor and unqualified forgiveness being given away for free, especially when the recipients aren’t the most deserving. “What’s the catch?” we inquire. “There’s always a catch!” In my experience, the so-called “problem” with grace is that we are so scared of how free it is that we often look for ways to tone it down, which just ruins the whole thing. Where there is no “catch” or “fine print” to be found, we make up our own, bankrupting the gift of grace in the process. “If it’s by grace,” the apostle Paul says, “it is no longer by works, otherwise grace would no longer be grace” (Rom. 11:6). God’s grace cannot be toned down nor can it be conditioned, especially not by the likes of us. This, by the way, was the precise point of contention that prompted Jesus to convey these parables in the first place.

Grace Is Offensive

The key to understanding Luke 15 is found in the first two verses, where Luke tells that “tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near” to Jesus, causing the scribes and Pharisees to grumble and mutter under their breath, “This man receives sinners and eats with them” (Luke 15:1–2). A recurring theme throughout Luke’s Gospel is how earnestly he reveals the inclusivity of God’s kingdom through the window of Jesus’s approachability. Bereft widows, frail lepers, and even well-known sinners, like tax collectors, are welcome. None are dismissed or turned away, a development that was a constant thorn in the Pharisees’ side. When Luke says that “tax collectors and sinners were drawing near” to Jesus, the gist is that this wasn’t a one-time thing. This was happening constantly, a fact that aggravated the scribes and Pharisees to no end.

The religious aristocrats couldn’t jive with what this renowned Rabbi from Nazareth was doing, especially since he was doing it all in the auspices of doing the will of God the Father. He had a habit of fraternizing with all the wrong sorts of people: social outcasts, cultural pariahs, and the religiously unclean (Luke 5:30). These were the sort of folks he welcomed with open arms. The Pharisees were so “scandalized,” R. C. H. Lenski notes, “because Jesus did not treat these disreputables as they did. In their holiness they scrupulously kept their skirts clean of any and all open sinners and thus clashed with Jesus on this point.” There was no aura or vibe surrounding Jesus that would deter the unworthy from coming close to him. Indeed, they were the precise reason why he had come (Luke 5:31–32).

As it is, the Pharisees’ outcry is actually true. “Can you believe this guy?” they complain. “He’s not only hanging around with prostitutes and tax agents, he’s even attending their dinner parties! The nerve!” Jesus, overhearing this, retorts, “Yep, you’re right, and if that upsets you, you ain’t seen nothing yet.” “So,” Luke reports, “he told them this parable” (Luke 15:3). Each of these stories—the lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son—is like a face of a diamond being held under a light. The more it’s turned, the more light it refracts, causing its brilliance to be that much more apparent. This, in a way, is what’s happening here; only Jesus is the jeweler, and the diamond is grace. As each story unfolds, so, too, is the grace of God unfurled.

The Relentless Search of Grace

Integral to each story is the pain of losing something or someone, a fact that becomes apparent once you notice that the same word for “lost” appears eight times throughout (Luke 15:4, 6, 8, 9, 17, 24, 32). The connotation is much more urgent than you might think, though. “Lost” doesn’t mean simply misplacing something, like your keys or the television remote. Rather, “lost” implies being in a state of deprivation, devastation, and want. Either through unfortunate circumstances or its own choices, what is lost has been cut off from life and is on the brink of ruin. A lonesome sheep that gets separated from the rest of the fold won’t be able to find its way back. Sheep, of course, aren’t the smartest creatures in the animal kingdom. They are generally dumb, defenseless, and easily distracted. Apart from the attention of a careful shepherd, they are prone to wandering off, which is why the biblical metaphor that sinners are just like sheep who “have gone astray” is both so insightful and unflattering (Isa. 53:6; Ps. 119:176).

Jesus, however, evokes this very common occurrence of a sheep getting lost to highlight the response of the shepherd. Whether you were a hired shepherd or the owner of your own flock, losing a sheep was a big loss. After all, this was your livelihood at stake. The only sheep herder who wouldn’t do this is probably not worthy to be called a “shepherd,” which explains Jesus’s rhetorical question (Luke 15:4). But as it is, the shepherd in Jesus’s story goes after his sheep “until he finds it.” There’s no limit to his searching. He won’t stop until he reclaims what is lost. Much like the woman who lost a whole day’s salary, the search isn’t over till the coin is found (Luke 15:8). There’s no quitting or giving up the search until what was lost is recovered, which is the very definition of relentless.

“Relentless” refers to the quality of persisting without giving up, slowing down, or being discouraged, no matter the obstacles and no matter what the cost. Both the shepherd and the woman show us this relentlessness, but so, too, does the father of the prodigal son, even though it’s easier to miss. In verse 20, Jesus arrives at the most poignant and profound moment in the history of storytelling. After frittering away his inheritance and reaching rock bottom in the form of a pigsty, the prodigal son comes to himself and resolves to go back home and beg for a crumb of his father’s mercy. “But,” Jesus tearjerkingly tells us, “while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him” (Luke 15:20).

Although it isn’t explicit, the image Christ paints for us is of a father searching the horizon, morning and evening, keeping his eyes peeled on the driveway, hoping one day he’ll see his long-lost son coming home. This is what the gospel says is true of our Savior, too. God’s Son arrives and pursues sinners with a grace that is relentless. He comes in search of you, and he won’t stop until he finds you, until he has you, even if he has to die in the process. “God pursues us relentlessly,” David Jeremiah once wrote, “he will not give us up, and once he has captured us, he won’t let us go.” Jesus, you see, is the embodiment of God’s relentless grace, which spies out sinners and goes after those who are lost and cut off from all life and all hope. “The Son of Man,” Jesus himself says, “came to seek and to save the lost” (Luke 19:10). Like a sheep that has gone astray or a coin that has been misplaced, we can’t and won’t find our way back on our own. We are in desperate need of someone to find us, which is exactly what the gospel tells us Jesus did.

The Joyful Surprise of Grace

Alongside the pattern of losing things is the sequence of those things being found (Luke 15:5, 9, 23–24). It is this note of finding or recovering that which was lost that always triggers joy. Indeed, as important as the theme of losing something is to each story, even more important is the joy that ensues when what was lost is found. (For what it’s worth, just like “lost” appears eight times, notes of “rejoicing” or “celebrating” occur eight times as well.) The shepherd who relentlessly pursues his lost sheep is so ecstatic that he throws a “block party” to celebrate (Luke 15:5–6). He returns home and invites the whole neighborhood to “rejoice with [him].” The joy of finding and reclaiming what was lost was so profound that he had to share it with others. He couldn’t keep that ecstasy to himself.

The same is true with the woman who finds her lost coin (Luke 15:9). She can’t contain her joy either, so much so that she calls everyone over for a dinner party. The grace of recovering that which was lost is that which generates the deepest notes of joy. In other words, grace and joy always go hand in hand. This, of course, is profoundly seen in the story of the prodigal son: “But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet. And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate. For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to celebrate” (Luke 15:20–24).

The father’s joy is almost palpable, leaping off the page and into our hearts. As soon as he’s through embracing his son, he promptly orders his staff to throw a huge celebration, complete with a roasted ox shoulder as the main course. And when Jesus tells us that “they began to celebrate,” he means it. The whole town is feasting and partying, to the point that as the older brother approaches the house, he hears their partying and dancing from all the way outside (Luke 15:25). This is just what grace is and does. Grace is the great instigator of joy. It is not only the gift that keeps on giving, but also the gift that arouses the sincerest and most spontaneous strains of delight, a point which Jesus leans into because of the Pharisees’ initial reaction. (Not for nothing, the word for “grumbling” Luke uses is the same LXX word for the unbelieving murmurs of the Israelites in the wilderness, cf. Exod. 15:24; 16:2, 7–9, 12; Num. 11:1; 14:2, 27, 29; Deut. 1:27.)

“The Pharisees and the scribes grumbled,” we’re told (Luke 15:2). They were beside themselves at Jesus’s ready reception of such notorious sinners. Since they saw themselves as experts in righteousness, they needed no repentance, to the point that they looked down on those who did. Their so-called “righteousness,” which was little more than self-derived religiosity, did nothing but stifle their joy. They were so self-righteous and self-serious that they resorted to complaining and griping at Jesus’s extension of compassion to the down-and-out, which is why Jesus was so adamant on conveying the heavenly celebration that ensues every time a sinner repents (Luke 15:10). In fact, he tells them that there is more joy in heaven over one repentant sinner than over ninety-nine self-righteous studs (Luke 15:7).

This corresponds to what the father tells the older son: that it was “fitting to celebrate” the prodigal’s return (Luke 15:32). “It’s sometimes hard,” Dale Ralph Davis comments, “to keep dignity intact when heaven throws parties and angels exchange ‘high-fives’ over a repentant sinner (vv. 7, 10).” Accordingly, the older brother serves as a stand-in for all those who don’t need to repent, not that they don’t, but that they think they don’t. In that way, Jesus holds up a mirror to the Pharisees, as if to say, “This is you. You’re a bunch of joyless sad-sacks!” And why were they so joyless? Why were they grumbling? One word: grace.

To those who think they don’t need it, grace will always seem outrageous and offensive. But to those who know just how desperate they are for it, grace will always come as a relief, which paves the way for rejoicing. “Grace,” Dave Zahl writes, “is an affront to the deserving, but to the empty-handed, it is the Big Relief.” “For people who think they’re good, grace is frustrating,” Tullian Tchividjian once said. “For people who know they’re not, grace is freeing.” The grace of God is the greatest incentive for joy in the history of the universe. It’s the surprising open invitation to a party already in progress.

The Willing Sacrifice of Grace

A simple fact that is quite illuminating to the narrative is that each of the parties Jesus mentions had to be paid for. The shepherd comes back home with his lost sheep draped over his shoulders and throws a party on his own dime (Luke 15:6), as does the woman who, after finding the misplaced coin, is quick to spend that coin celebrating with friends and neighbors (Luke 15:9). Neither the shepherd nor the woman is reluctant in doing so. Rather, they are more than willing to incur the cost, which lets us know that what we’re witnessing is divine grace at work. After all, as Dave Zahl says, “grace, for it to qualify as divine, involves an element of sacrifice.” What makes moments of grace so profound and surprising is that the one showing or giving grace feels the cost, deeply, and gladly goes through with it anyway.

This is, perhaps, most pronounced when Jesus gets to the part where the prodigal son returns home (Luke 15:20–24). Even though he has rehearsed his “repentance speech” countless times, his father barely lets him get through the first sentence without interrupting him; that’s how thrilled he is that his wayward boy has come home. And without the slightest hesitation or second thought, he proceeds to arrange a feast for the whole neighborhood at his expense, the centerpiece of which is a “fattened calf.” The significance of this is probably lost on us, especially since we can stroll into Walmart and pick up a ribeye to throw on the grill anytime we want. In those days, a fattened calf wasn’t a common farm animal. This was a luxury animal, usually only found in wealthier households, specifically set aside for special occasions. A fattened calf would be fed a special diet and housed in a special location to raise the tenderest meat possible. This wasn’t a Big Mac. This was meat that had been nurtured and meticulously cared for over a long period of time. To slaughter and prepare a fattened calf, therefore, was a sign of extravagance and exceptional hospitality. Receiving an invitation to a dinner party where this was the main course meant you were in for what might be a once-in-a-lifetime feast.

The point is that the father is more than willing to make this sacrifice. His lost son was recovered; his boy who was as good as dead was “alive again” (Luke 15:24, 32). It was precisely all this extravagance that frustrated the older brother, who viewed it all as a waste (Luke 15:28–30). In his eyes, his dad was going over the top. The whole thing was a bit excessive and far too lavish, especially when the guest of honor was his derelict younger brother. “Why are you wasting this on him? Don’t you know how much I’ve done? Don’t you see how good I’ve been?” The father, though, who had left the party to try and convince his eldest to stop pouting, was willing to risk being labeled a “rude host,” all so that he could meet his boy right where he is. This, too, is grace.

That’s just who this father is. In one of the most memorable and affecting scenes in the history of storytelling, the father of the prodigal son spots his wayward boy and sprints down the driveway to hug him (Luke 15:20). For a patriarch of a “well-to-do” family to scamper in such a juvenile manner was considered highly undignified, not to mention the fact that he was running to embrace one so unworthy and undeserving of such displays of affection. But that’s just what grace does. God’s grace is unashamed to meet us right where we are, in the pits of failure, shame, and disaster. Grace, Horatius Bonar once wrote, “meets the sinner on the spot where he stands, and it approaches him just as he is.” It comes right up to him and showers him in unceasing and unmerited favor. “God takes the first step,” concurs Dave Zahl, “lavishing grace on antagonistic men and women before they can prove themselves worthy.”

Consequently, grace can only rightly be understood through the extravagant sacrifice of Christ for us. The best glimpse of God’s grace is found in the person of Jesus. In what can only be described as a joyous surprise, God in Christ gladly gives himself up, all so that sinners can be reconciled and reclaimed. He comes to us in the midst of our ruin and brokenness and lays down his life so that we might be redeemed, recovered, and found. This, to be sure, is the message we are compelled to preach from Luke 15—not some watered-down sermon of mercy that is freighted with conditions and provisos, but the relentless, joyful, sacrificial grace of the Father as demonstrated in the life, death, and resurrection of the Son. In so doing, preachers fling wide the doors to a celebration that’s already underway, with the accompanying announcement that all are welcome inside.

Footnotes

David Zahl, The Big Relief: The Urgency of Grace for a Worn-Out World (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2025), 9.

BackR. C. H. Lenski, The Interpretation of St. Luke’s Gospel (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1961), 794.

BackThis is why I prefer to call this chapter “The Parable of Lost Things.”

BackDavid Jeremiah, Captured by Grace: No One Is Beyond the Reach of a Loving God (Brentwood, TN: Integrity Publishers, 2006), 21.

BackDale Ralph Davis, Luke 14–24: On the Road to Jerusalem, Focus on the Bible Commentary Series (Ross-shire, England: Christian Focus, 2021), 35.

BackZahl, 23.

BackTullian Tchividjian, One Way Love: Inexhaustible Grace for an Exhausted World (Colorado Springs, CO: David C Cook, 2013), 47.

BackZahl, 15.

BackHoratius Bonar, “God’s Purpose of Grace,” Kelso Tracts (London: James Nisbet & Co., 1851), 31:7.

BackZahl, 15.

Back