The following was originally delivered as a breakout session at the 2023 Here We Still Stand Conference hosted by 1517 in San Diego, California. May your heart and soul be enriched and encouraged as you read these words.

The eminent Oxford don, C. S. Lewis, famously attributed his faith in Christianity to the realization that the Christian gospel “is simply a true myth.” In a letter to the Anglican bishop and his longtime correspondent, Arthur Greeves, Lewis confesses:

“What [Hugo] Dyson and [J. R. R.] Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of sacrifice in a Pagan story I didn’t mind it at all . . . if I met the idea of a god sacrificing himself to himself I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it . . . the idea of the dying and reviving god (Balder, Adonis, Bacchus) similarly moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. The reason was that in Pagan stories I was prepared to feel the myth as profound and suggestive of meanings beyond my grasp even [though] I could not say in cold prose ‘what it meant’. Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened” (Dorsett, 56).

Lewis’s epiphany is reminiscent of Job’s eruption of hope in a mythic Redeemer who would one day put all of his brokenness back together again. A word or two is, perhaps, in order to clarify what Lewis means by “myth.” Oftentimes, a straight line is drawn between myth and fable, with the result being that myths are generally regarded as fiction. Be that as it may, properly understood, a myth needn’t be discarded wholesale simply because of its mythic qualities. “Myth, in general,” Lewis writes in his treatise on Miracles, “is not merely misunderstood history . . . nor diabolical illusion . . . nor priestly lying . . . but, at its best, a real though unfocused gleam of divine truth falling on human imagination” (134). In this paradigm, a myth is a revelation of the divine that has been transmitted through the packaging of a tangible narrative. Applying the term “myth” to the Christian faith, therefore, shouldn’t catch us off guard as much as it might initially. As Lewis says elsewhere, those who believe in the gospel of God “must not be ashamed of the mythical radiance resting on [their] theology” (God in the Dock, 67).

With this treatment of a true myth in mind, we are better able to understand the meaning behind Job’s enigmatic exclamation, “For I know that my Redeemer lives” (Job 19:25). Throughout chapter 19, Job’s language takes on a conflicted posture of acknowledging his misery while at the same time hoping for something or someone beyond him. This particular dialogue comes from Job at what is roughly the halfway point of the discussion in which he and his so-called “friends” are engaged. If you recall, Job’s life has been thoroughly upended. All of his assets, securities, and posterity have been wiped out, leaving him with next to nothing, except for some “loathsome sores from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head” and some gnarly scars where he cut himself with broken bits of pottery in order to deal with the cavity of suffering that had seemingly swallowed him whole (Job 2:7–8).

Unhelpful Reasons for Job’s Mess

Everything that Job possessed was sufficiently wrecked and ruined, and the worst part was he had no idea why. What makes the Book of Job so intriguing, though, is that you and I do know—we are told from the get-go why this sorrowful squall descended upon our title character. The first two chapters record an exchange between God and Satan, and the “wager” that was made concerning the Lord’s “servant Job.” “Stretch out your hand,” Satan snaps, “and touch all that he has, and he will curse you to your face” (Job 1:10–11; 2:4–5). Job, however, is completely unaware of those scenes in the heavens. For all he knew, he was merely having a “terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day.”

Job’s friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, eventually arrive and sit with him in a deafening week-long silence (Job 2:11–13). In their quiet company and consolation, Job gives vent to a series of devastating confessions, cursing the day he was conceived and bemoaning the dreadful gloom that had overtaken him. So pointed is his grief that he actually wishes he could go back to the day of his delivery from his mother’s womb and die right then (Job 3:11). But as our penultimate sufferer pours out his pain, his so-called “friends” decide that it is up to them to “figure out” and discern the reasons behind their neighbor’s suffering. This is what makes the Book of Job so tedious since it is, essentially, a collection of conversations between a man enduring the severest of all suffering and his supposed friends who have taken up the task of determining what occasioned his awful ordeal.

The logic of Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar insists that Job must have done something amiss, something to anger the gods, otherwise, the fates would not be dealing with him so agonizingly. “Job’s accusers,” writes David C. Deuel, “based on their rigid perception of the retribution principle, extrapolate that Job must have sinned. According to their narrow perception of God’s retributive activity, no one suffers for being innocent—Job must be guilty” (98, emphasis mine). According to his friends, Job was reaping what he had sown. “Those who plow iniquity and sow trouble,” Eliphaz says outright, “reap the same” (Job 4:8). By that logic, Job was getting what he deserved, a claim which undoubtedly made his agony all the more agonizing. The remainder of the book goes on like this for quite some time, as Job’s “friends” prosecute his suffering and anguish in order to uncover his complicity in it all.

Hope, Abandoned

Turning the page to chapter 19 introduces us to a man whose patience has started to thin. As his buddy wraps up a lengthy description of what an “unjust man who does not know God” looks like (Job 18:5, 12–18), Job’s heart is devastated once more as Bildad suggests that Job fits that description to a T (Job 18:21). It’s at this point that Job proceeds to unload all of his pent-up anguish both on his so-called “friends” and his God: “How long will you torment me and break me in pieces with words? These ten times you have cast reproach upon me, are you not ashamed to wrong me? And even if it be true that I have erred, my error remains with myself. If indeed you magnify yourselves against me and make my disgrace an argument against me, know then that God has put me in the wrong and closed his net about me” (Job 19:2–6).

Listening to Job rehearse his grief invites us to see that he was in the most lamentable place imaginable. From his perspective, his current predicament was one that was handed to him by God himself (Job 19:6). He understood the culprit behind his calamity to be none other than God himself, an allegation that sounds frighteningly true, especially in light of the appalling description he gives of his despair (Job 19:7–9). As Job cried out for help, there was no sound. There was no response. Because no one was listening. He was all alone in the darkness, stripped of glory, destitute of all that had once given him security and standing. Things for Job felt like a pulverized mess, leaving him with little else to do but sit and fill the rubbled room with his tears. His life was upended; his hope “pulled up like a tree” (Job 19:10). Everything that he had counted on was sufficiently uprooted, snapping every stable mooring he once enjoyed.

Everywhere Job looked, he seemed to find new evidence of God’s ferocity. He had come to believe that he had been caught in the vengeful crosshairs of his Maker’s wrath, with each new ingredient of suffering besieging him like battle-hardened soldiers invading a citadel (Job 19:11–12). On top of all that, he was forced to watch as each cherished relationship, which should’ve served as reservoirs of comfort and relief, slowly disintegrated all around him (Job 19:13–19). The appalling horrors that rained down on his life seemed to push those who were once close further and further away. He laments that his sorrow has even seeped into his marriage (Job 19:17). He suffers as a stranger, as a foreigner in his own home, with no comfort or company of which to speak. He’s to the point where he’s barely hanging on by the skin of his teeth (Job 19:20).

Hope, Rediscovered

You are, perhaps, wondering right about now why I am taking you through all of this. What is helpful and hopeful about rehashing Job’s nightmarish suffering? As it turns out, this glimpse at the grief-stricken Job discloses what is a sufferer’s only hope. What does hope look like for those who are suffering? Where should we who are enduring the “dark night of the soul” look for grace and consolation? To answer these inquiries, we have to ask another question—namely, what does someone in Job’s situation actually need? Instinctually, we often resort to offering a myriad of reasons or answers or explanations that seek to make sense of our suffering; that is, we respond to suffering like Job’s with facts. And, certainly, the facts of our upheaval can offer a modicum of relief, but sufferers are desperate for far more than facts. Job’s deepest need during his “dark night of the soul” was for something truer and better to not only give him reasons, answers, or explanations for his situation but also to repair his situation and suffuse it with the hope of restitution. And it was precisely the mythic hope of a living Redeemer that bathed Job’s darkness in the light of heaven. “For I know that my Redeemer lives,” he exclaims, “and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. My heart faints within me!” (Job 19:25–27).

It is at this point that I submit that much of modern scholarship has failed us and miserably so. If you were to scour the journals of academia or the commentaries of learned theologians, as I have done, you would be greeted by an array of meditated reasons why this sudden burst of hope from Job is not and cannot be a reference to the Messiah, to Christ. Job’s “redeemer” or “vindicator,” they say, is merely a reference to some other human relation in Job’s family who would take up the role of Job’s kinsman-redeemer to preserve Job’s name and legacy. This person would act as Job’s executor, ensuring that the epitaph of his life wouldn’t be preoccupied with the suffering and sorrow that plagued his final days (Job 19:23–24). In James K. Zink’s essay, “Impatient Job: An Interpretation of Job 19:25–27,” he cites A. R. Johnson, who attests, “It is the function of the גָּאַל [kinsman redeemer] to protect the life or vitality of both the individual and the kin-group and thus preserve their standing in society by keeping intact their essential unity or integrity” (150).

In “Death, Disinheritance, and Job’s Kinsman-Redeemer,” an essay by Matthew J. Suriano for the Journal of Biblical Literature, we are told: “The passionate speech in [Job] 19:23-27 evokes the protagonist’s confidence that, after his death, a kinsman-redeemer (v. 25) will perform the proper rituals on his behalf in order to preserve Job’s name and patrimony for posterity . . . The cultural background of v. 23-24 and 26-27 indicates that v. 25 describes a living person who would act on behalf of the righteous sufferer once he (Job) had passed away . . . What Job responds to is the threat of postmortem annihilation, described as the ‘dreaded death after death,’ which is essential to have one’s name extinguished from memory . . . Although it is never directly stated in these chapters, the implied and ultimate threat of final retribution is the eradication of his name. It is Job’s kinsman-redeemer, through the performance of his duties, who will act against this threat and effectively preserve Job’s name” (50, 60, 64–65).

I say this with everything that is holy in me: I don’t very much care what the academics say. Indeed, I co-sign J. I. Mombert’s sentiment when he once wrote: “I cannot resist the conviction that the passage is decidedly eschatological, and stands out in solitary grandeur as an ancient prophecy, or poetic vision of a resurrection” (38). The modern insistence that Job’s surge of hope has nothing to do with a future heaven-sent Redeemer undercuts this confession and warps it from a guttural albeit hopeful lament into nothing but a languishing shriek. Setting aside, for the moment, the fact that most if not all of the early church fathers—such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Augustine of Hippo, and St. Jerome, for example—interpreted Job’s redeemer as none but Christ, to contend otherwise seems untenable with any faith tradition that has been handed down since the days of Adam. Ever since that fateful moment in Eden, those who belong to the Lord have been bundled up in the promise that a Redeemer and Rescuer would show up to crush the head of the serpent (Gen. 3:15). The vindication of every suffering and sorrowing sinner has always been tethered to one who would set everything right by enduring violence on their behalf.

The Comfort of Christ’s Face

Whatever Job knew or believed when he cried, “I know that my Redeemer lives,” he knew “only in the dim distance of remote history,” as the nineteenth-century English librarian Josiah Forsall put it (10). To imbibe the words of the writer of Hebrews, he saw his hope from afar (Heb. 11:13). All of which to say, Job’s rhapsody of hope is only sensible in light of the resurrection. This is the essence of his confession and his trust. While it might be naïve to insist that this prayer is in some way a direct prophecy of the resurrection, it is decidedly and unmistakably downstream of an indirect myth (in Lewis’s rich sense of the term) of a resurrection; that much is certain. And it is precisely the true myth of the resurrection that has imbued the people of God with hope despite their apparent hopeless surroundings.

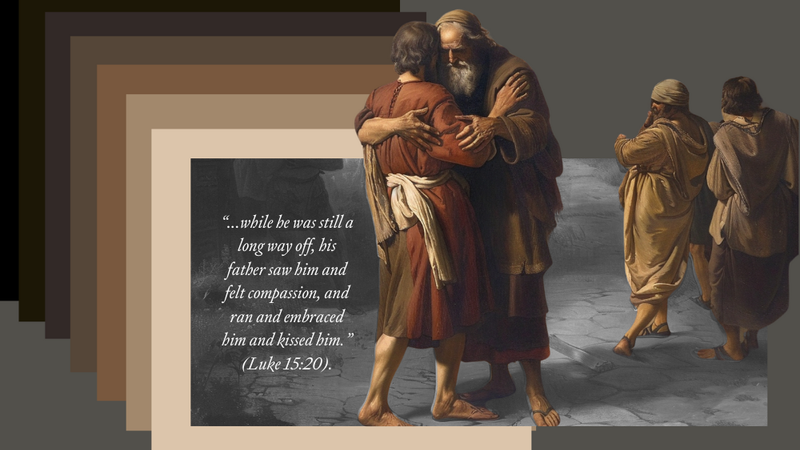

Job’s faith, however feebly, clung to the hope that his Vindicator was not only alive but also was, even at that moment, standing on his behalf in the heavens (Job 19:25). Even if he couldn’t make sense of it all, there was one who could and would—and one day, he would see his Redeemer with his own eyes, not as “another” (Job 19:27), not as a stranger, but as a Friend. You and I, likewise, won’t always be able to discern the purposes behind our darkest days. But the “hope beyond hope” that gives peace to every weary sufferer is the hope of a Friendly Face that greets us and draws near to us in the midst of our suffering and sorrow. And that face is none other than the face of your Redeemer.

The pain, sorrow, and agony you and I endure are all too real, and we should never pretend that it isn’t. But just as real as our suffering is, there is a real Person who meets us in it. It is Christ who shows up for you to be with you in the very worst of your troubles and tribulations. He is your incarnate sufferer and substitute, the one who embraces all of your griefs, pains, and agonies, so much so that he takes them all as his own. In the person of Jesus, we are made to see the God who takes on a body, who shares in flesh and blood, in order that he might “taste death for everyone” and therein “destroy the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil” (Heb. 2:9, 14). To borrow Lewis’s turn of phrase from one of his essays in God in the Dock, the gospel is the good news that the myth of Job’s Redeemer has become a fact in the battered and bruised face of the God who suffers and dies while being pegged to a cross. “As myth transcends thought, Incarnation transcends myth,” Lewis writes. “The heart of Christianity is myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the Dying God, without ceasing to be [a] myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens—at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences” (God in the Dock, 66).

What makes the gospel so remarkable for those caught in the throes of suffering and sorrow is that its appeals aren’t to some far-off, nebulous force. Christian hope isn’t vague. Rather, it is incarnate—it is hope that lives and breathes and bleeds out for you (1 Pet. 1:3). It is wedded to the sublime announcement that, as Lewis attests, “God really has dived down into the bottom of creation, and has come up bringing the whole redeemed nature on His shoulder” (God in the Dock, 87). The gospel says that there is a Person upon whom you can fall during the severest bouts of stress, worry, fear, and doubt. And that Person will never turn you away.

In a 2019 sermon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., the late Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson concluded his sermon by saying, “At the end of all our striving and longing, we find, not a force, but a face. All language about God is metaphorical. But the metaphor became flesh and dwelt among us.” This is the hopeful note that echoes throughout our lives. From St. John to C. S. Lewis, Christian hope is encapsulated and embodied in the metaphor that became a man who became “obedient to the point of death even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:8). The enduring mystery of the gospel, therefore, is not really that ambiguous. It is the exquisite fact that even in seasons of doubt and despair, the rumor of grace is whispered in our ear by a living person, by he who is the epitome of the Father’s heart—that is, by none other than the Word become flesh. The “Myth become Fact” is none other than Christ himself, whose “mythical radiance” participates in all the appalling horrors of our factual existence that we might be imbued “with all joy and peace in believing” (Rom. 15:13). Indeed, it is precisely this “mythical radiance” of the Christ of God that suffuses our daily lives with the certainty that our future as well as our present is held together by him alone (Col. 1:17).

Whatever theoretical or conceptual ideas to which we surrender in despair, the Christian faith offers something wholly different. The gospel offers not a force, but a face; not a philosophy, but a Person; not a myth only but a “Myth become Fact.” In the agonizing pit of grief and loss and doubt, faith binds us to the one who lived, bled, died, and rose again for every sinner and sufferer who’s ever existed. And he is living for us even still. What do we do, then, with our grief? We cry and pray. What do we do with all these tears? We let them flow, knowing that the God of heaven has come down to the dirt to catch every one of them (Ps. 56:8) and promises to one day wipe them all away (Rev. 21:4). Myth became Fact in the person of Jesus, who everlastingly embodies the providential concern and gracious care of the Father for every despondent sufferer. Even now, he is concerned for you, and he is keeping you forever by his grace. And that’s a fact.

Works cited:

David C. Deuel, “Job 19:25 and Job 23:10 Revisited an Exegetical Note,” TMSJ 5:1 (Spring 1994): 97–99.

Lyle W. Dorsett, editor, The Essential C. S. Lewis (New York: Scribner, 2017).

Josiah Forshall, A sermon, preached in the chapel of the Foundling Hospital on the 7th April, 1839; being the Sunday immediately succeeding the funeral of Samuel Compton Cox (London: Woodfall & Son, 1841).

C. S. Lewis, God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, edited by Walter Hooper (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1970).

C. S. Lewis, Miracles (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1978).

J. I. Mombert, “On Job xix. 25–27,” Journal of the Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis 2:1 (1882): 27–39.

Matthew J. Suriano, “Death, Disinheritance, and Job’s Kinsman-Redeemer,” Journal of Biblical Literature129:1 (2010): 49-66.

James K. Zink, “Impatient Job: An Interpretation of Job 19:25–27,” Journal of Biblical Literature 84:2 (1965): 147–52.