Most people with a basic knowledge of English history have heard the name of Katherine Parr, Henry VIII’s sixth and final wife, the only one in the list that could be said to have “survived” without experiencing a divorce. Few, however, are familiar with her story, and even fewer with her writings.

In fact, her unique relationship with an already aging king, her narrow escape from accusations of heresy, and her perplexing choices after Henry’s death given rise to a number of interpretations of her history which have obscured the facts. For those unfamiliar with the life and writings of Katherine Parr, those interpretations may seem plausible. For Don Matzat, they did not.

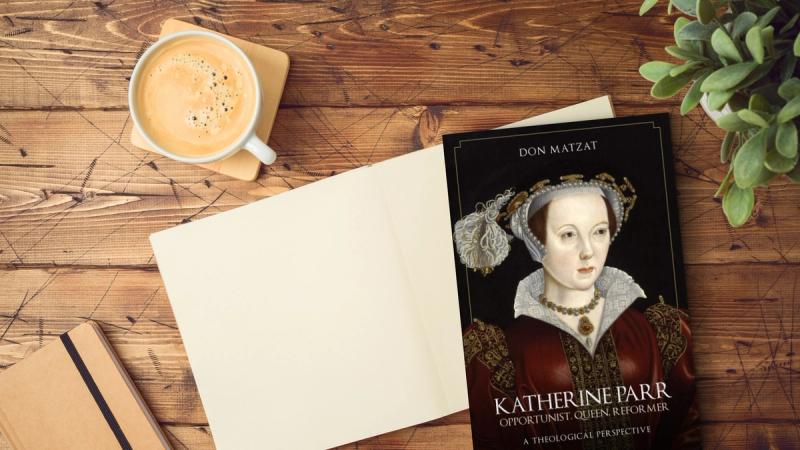

Matzat’s book, Katherine Parr: Opportunist, Queen, Reformer: A Theological Perspective, is the fruit of a long and diligent investigation to find answers to some gnawing questions, primarily, why did this intelligent queen, so influential in her day, become almost forgotten in the following centuries? And why has her literary masterpiece, The Lamentations of a Sinner, been so neglected?

In his book, Matzat describes his research, his discoveries, and his conclusions. Though Katherine Parr is not meant to be an exhaustive biography, and though Matzat states from the beginning that he is not a historian, he depicts a lively account of the adventurous life of this queen. Equally gripping is his description of the historical setting of 16th-century England and of King Henry’s relationship with his six wives.

But Matzat has a definite goal, and rarely strays from it: he wants to point out when and how Katherine Parr understood that justification comes by faith alone, and how clearly and cogently she expressed this discovery in The Lamentations of a Sinner (1547).

Many Protestant hagiographers have depicted Parr as a religious reformer who married the aging, sickly Henry with the goal of promoting the Protestant Reformation at court and, eventually, throughout the country. Matzat gives ample proof of the contrary. When Parr married Henry, Maztat argues, she was still faithful to her Roman Catholic upbringing.

This is clear in her earliest publication, Psalms or Prayers, an English translation of bishop John Fisher’s Latin Psalms, which she published anonymously in 1544. The same theological stance is also evident in her second book, Prayers or Meditations, printed the following year—the first book published in England by a woman under her own name.

If the language of religious reform is found in these books, Matzat explains, it can be attributed to the strong influence her contemporary Desiderius Erasmus exercised on England at that time. Like Erasmus, Katherine challenged herself and her readers to greater devotion to God.

It’s in the clear distinction between Erasmus and Luther (and, consequently, between Parr’s earlier writings and The Lamentation of a Sinner) that, in my opinion, Matzat’s book has the greatest value. He is not the first one to address the gradual evolution of Parr’s theology (other books, though few, have recognized it), but he is the first, to my knowledge, to explain in concrete and unclouded terms the radical divergence between the two theological positions in her life.

This is a subject upon which Matzat writes with passion. “In assessing the religious landscape of sixteenth-century England,” he says,” what is most frustrating is the failure of historians and biographers to define terms and to distinguish the reform touted by Erasmus and his humanist disciples, including both King Henry and Queen Katherine, from the radical views of Luther and the Protestant Reformation” (75).

For Matzat, this distinction is absolutely essential to a proper understanding of the Protestant Reformation, and it hinges on Luther’s proclamation of the doctrine of justification by faith alone—a doctrine that Matzat explains exhaustively.

The fact that generations of Christians have neglected to see this distinction is reflected in the preference readers have given to Parr’s earlier writings rather than to The Lamentation of a Sinner (where she expounds this doctrine of justification). It is also reflected in the compromising attitude of many Christians throughout history. For example, Matzat says, “The twentieth-century ecumenical movement has attempted to restore the Erasmian notion that the importance of doctrinal truth should be sacrificed at the altar of unity and compromise. In so doing, the distinctiveness of justification by faith has been marginalized” (152).

Matzat believes that Parr came to a clear understanding of justification by faith alone only around 1546. This is probably when she started to write The Lamentation of a Sinner. Due to its controversial contents, however, she only published it in 1547, after Henry’s death.

The uniqueness and value of Parr’s work is well detailed in Matzat’s book, both throughout the text and in the appendix, which is “added for those who wish to pursue in greater detail the affirmations contained in the Lamentation of a Sinner” (215).

He also provides an adaptation of The Lamentation of a Sinner, based on the 1547 edition of the original work. Although an adaptation in modern English, together with the original version, is available in Jane Mueller, Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence, Matzat found that version still too close to what he called “‘King James speak.’ I wanted to take it a step further, and hopefully put it into English the average person might readily understand” (12).

This decision is indicative of the whole tenor of the book. This is not an academic book (scholarly minds might want to follow up with Mueller’s volume). In fact, Matzat is often comfortable with giving personal opinions and including personal stories, particularly in the appendix.

“I suspect the primary criticism my work will receive is that I place an undue emphasis on Katherine Parr’s discovery of justification by faith,” Matzat admits (146). I didn’t find the emphasis “undue,” although the text may sound repetitive at times.

The book includes sixteen pages of beautiful photographs of people, places (interiors and exteriors), and objects such as an original letter by Parr and copies of Parr’s Prayers or Meditations. The bibliography at the end will direct the reader to texts mentioned in the book, including other versions of Parr’s works. In his introduction, Matzat states his hope that his readers “will be informed by the remarkable life of Katherine Parr; edified by her Christian witness; and instructed by her clear teaching” (19). I believe he has amply met his goals. In my case, he has answered many questions I had about the queen’s life, highlighted the influence Erasmus continues to have on Christian thought, and helped me to read Parr’s writings with fresh eyes and a greater awareness of her theological growth.

Simonetta Carr is the author of numerous books, including Broken Pieces and the God Who Mends Them: Schizophrenia through a Mother’s Eyes, and the series Christian Biographies for Young Readers (Reformation Heritage Books)