Joseph of Nazareth, the adoptive father of Jesus, is neglected in theology and biblical studies, but we come by it honestly. His obscurity in the tradition is more or less proportional to his obscurity in Scripture. There, he speaks not a word, nor does anyone speak to him (no human, that is), and after the Nativity and Boyhood Narratives, he is not seen again and is seldom alluded to (strongly suggesting he was dead before Jesus began his public ministry).

But neither is Joseph invisible, and the glimpses we catch suggest an extraordinary character. Though a poor carpenter, Joseph of Nazareth had a reputation as a “just man” (Matt. 1:19), a reputation he was willing to jeopardize by consenting not to divorce Mary and to adopt her child as his own. Like his Old Testament namesake, Joseph was a “dreamer” (see Gen. 37:19) who communed with angels and obeyed their commissions promptly: This obedience made him an effective protector of his family as they fled Herod and eventually settled in Nazareth, in the region of Galilee, where presumably Jesus was raised until he left home to seek baptism from his cousin, John, some sixty miles away. We can expect Joseph would have fulfilled the expectations placed on Jewish fathers at the time: He would have handed down his trade to Jesus, initiated him into Jewish ritual life, and so on. But what I wish to focus on here is how Joseph’s paternal love might have influenced the Messiah’s later teachings.

Father’s Day: A Day for the Fatherless

by Leon M. Brown

Sharing his personal story of growing up without his dad in his life, Brown asks us to reflect on the sober reality of a widespread absence of fathers in contemporary culture even as we celebrate their value. He urges us to remember and participate in God’s special care for the fatherless.

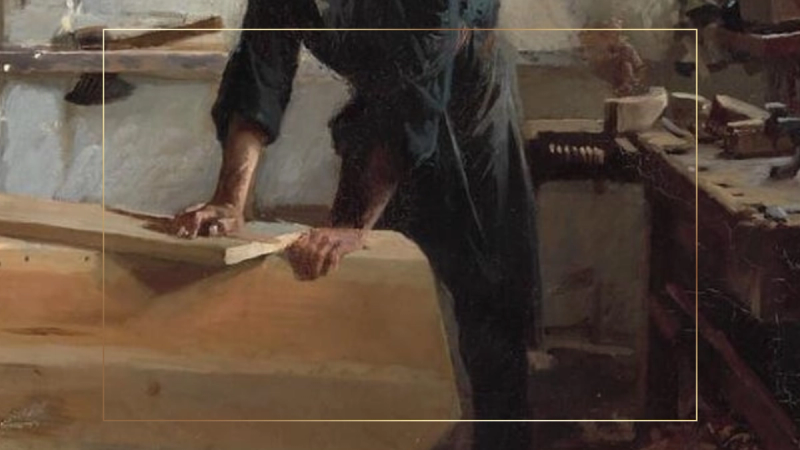

It is no scandal to suggest that Jesus, according to his humanity, required parental oversight in order to increase “in wisdom and in stature” (Luke 2:52), but the vast majority of reflection on this point has focused on Mary. She is cast in the tradition as Christ’s premier instructor, not Joseph. In the earliest complete biography of the Holy Virgin, likely written by Maximus the Confessor in the seventh century, the author counts her zeal for Scripture among her qualifications to parent the Son of God: “For she loved learning and was an excellent student: she was an expert in every good subject and filled with understanding of the divine Scripture and with all wisdom, because she was to become the mother of the Word and Wisdom of God.” In the late medieval period, artistic depictions of the Holy Family occasionally placed Mary off to the side, absorbed in the study of Scripture, while Joseph attended to the holy toddler. Centuries of Madonnas, which often feature mother and child perusing a Bible or a Book of Hours together, eliminate Joseph altogether. An implicit duality of roles emerges, where Joseph is tasked with the visible humanity of Jesus and Mary the invisible humanity. Joseph teaches Jesus how to walk and Mary how to pray; Joseph, carpentry; Mary, exposition of the Scriptures. Accordingly, the increase in Jesus’ “stature” is a credit to Joseph; his increase in “wisdom,” to Mary. While a modern audience might be too eager to extract principles on parenting or recommendations on gender roles from these artistic representations, the true motive behind them is Christological: Each parent represents one aspect of his humanity—Joseph the outer, Mary the inner—and so depictions of the Holy Family were meant to emphasize the full humanity of Christ.

There is biblical rationale for casting Mary as Jesus’ premier instructor. The author of Luke places the Magnificat in her mouth. In addition to being a moving song of praise, it trades masterfully in scriptural themes and language. Joseph demonstrates nothing so astute; in fact, he leaves no word on record. Between the two of them, Mary is more the teacher. But whatever historical veracity there is to the image of Mary as an “expert on Scripture,” we can still say with relative confidence that Mary’s role in rearing and educating Jesus was not immaterial, but that, as Edward Schillebeeckx says, “His human qualities and character were formed and influenced by his mother’s virtues.”

Calvin on the Lord’s Prayer

by Alan Maben

Maben explores Calvin’s discussion of the Lord’s Prayer particularly through the lens of its very first phrase, teaching us to call on God as “our Father” and to recognize ourselves as his adopted sons and daughters in Christ.

I wish to turn this same line of reflection, which Mary has enjoyed for centuries, on Joseph: What virtues of his formed and influenced the humanity of Jesus, and can we trace these in the Messiah’s later teachings? While this will require a serving of conjecture, I believe it can draw us into the text afresh while helping us see the life of Christ as a unity.

Perhaps with prolonged reflection and more exacting exegesis, any number of “Josephic contributions” could be identified in Christ’s teachings. But I wish to focus on one alone, since it seems to me the thing we can say with confidence; namely, Joseph must have taught Jesus what a father was.

Each of the Synoptic Gospels shows Jesus making his start by preaching in local Jewish synagogues. Particularly in this early stage, we would expect his audience to be primarily men. His preaching often appeals to the experiences of men. Some examples include,

- The Wicked Husbandman (Mark 12:1–11; Matt. 21:33–44; Luke 20:9–18)

- The Doorkeeper (Mark 13:33–37; Luke 12:35–38)

- The Lost Sheep (Matt. 18:12–14; Luke 15:4–7)

These three parables feature male characters in typically male occupations. However, a number of Christ’s parables fall within the horizon of female experience, including,

- The Yeast (Matt. 13:33; Luke 13:20)

- The Lost Coin (Luke 15:5–10)

- The Persistent Widow (Luke 18:1–8)

In the world of Jesus, the grinding of grain, the baking of bread, and the management of household finances were the responsibilities of women (cf. Prov. 31). Christ undoubtedly had women in his audience who could relate to these parables. This would have become more often the case the more openly he preached in the streets and the countryside, a point bolstered by the fact that women approached him while he was about (e.g., Matt. 15:21–28; Mark 5:21–43; Luke 7:11–17), just as he would occasionally approach them (e.g., Luke 13:10–17; John 4:1–26) or address them (e.g., Luke 23:26–31), and that he evidently had a cohort of women disciples who accompanied him beyond Galilee (Luke 8:1–3; 23:49). So the characters in his parables reflect his mixed audience.

Some scholars have argued that when Christ spoke women-specific parables, he was turning to address the women in his audience directly or even exclusively. This requires us to assume that the men of Jesus’ time would not have been expected to understand these teachings on the grounds that they involved women’s concerns and occupations. This would put us in the awkward position of asserting that Christ had one set of parables for women and another for men. A better explanation is that Jesus chose to draw material from the everyday affairs of both men and women that were observed by all and thus relied on a common cultural frame of reference.

Parenting in the Gospel

by Tedd Tripp

Tripp reminds Christian fathers (and mothers) of their calling to disciple their kids—but more than that, Tripp reminds us that “our hope is not our fidelity to the law of good parenting but to the power of the gospel. Our hope is the wonder of grace.”

The worlds of men and women were not totally isolated from each other. We must remember that Christ himself was male, yet this limited horizon of experience did not prevent him from accurately representing the interests of women in his parables. We can imagine Jesus as a boy witnessing the domestic drama of a wife who lived on his street organizing her neighbors into a search party for a lost coin. We can imagine after some hours he heard her joyous report that what had been lost had, at last, been found. We can imagine Jesus watching the other women celebrating with her and sharing stories of similar incidents. Perhaps Jesus had joined in the search party. Perhaps Jesus had been the one who found the coin. Perhaps the woman who lost it had been his own mother. Who can say? The point is the things he observed were the sort of things anyone in that society could observe. It was precisely the quotidian character of his parables that made them accessible to all his listeners, and it is again their quotidian character which suggests Christ crafted them from his own (utterly average) experiences and observations growing up in first-century Palestine.

At last, it seems reasonable to assume that Jesus’ experience of being raised by Joseph would have majorly influenced his concept of fatherhood. As it happens, Jesus says little about (earthly) fathers in the Gospels. (This may surprise us, since the Fatherhood of God is such a distinctive part of his ministry.) What’s more, his few statements are general, referring to fathers everywhere. Even so, it remains that in Jesus’ mind the direct reference for fatherhood was his own Joseph, as our fathers are for us. So in the few statements he does make, is it possible we detect a whisper of Joseph’s character?

In all cultures of antiquity, a “father” was a positive symbol, representing benevolent authority and clemency. Perhaps the most famous father in Jesus’ teachings, in his parable of the prodigal son, is also the most aligned with ancient ideals (Luke 15:11–32). Motivated by paternal affection, he readily forgives his children. (The shock of the parable is not that fathers are this way—Jesus’ audience already believed they were—but that the kingdom is this way.) He runs to welcome the youngest when he returns home, but also goes out to entreat the eldest when he refuses to join the celebration. This father is continuously seeking after his sons and acting for their welfare and concord. This father, however, is so idealized that we can detect no biographical trace on its polished surface.

Fortunately, the fathers in Jesus’ teachings are not all so immaculate. Immediately after instructing his disciples to directly address God as “Father,” he encourages them to make their requests with confidence: “Or which one of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a serpent?” (Matt. 7:9–10). Here Jesus means to speak of real fathers, “who are evil” (v. 11), as a foil to extol the perfection of divine Fatherhood: If even earthly fathers are this way, “how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask him!” (v. 11; emphasis mine).

Muscular Christianity

by Michael Horton

Being a faithful dad, and understanding biblical fatherhood, is inseparable from being a faithful man and understanding biblical manhood. Horton calls us to rise above reactionary stereotypes and caricatures when it comes to being a faithful Christian man (or dad).

The strong details in this teaching—a son, a serving of bread, an egg—are evocative. We can just imagine the boy Jesus, famished after playing in the sun, visiting Joseph in his carpentry shop, hands extended: May I have a fish, abba? Or a piece of bread? It could be that Jesus was recalling the experience of his own boyhood when he taught his disciples that even earthly fathers know how to give good gifts to their children; at any rate, the specifics are the strongest evidence that he is doing so. And we learn here what Jesus thinks about when he thinks of a “father”—specifically, an earthly one: He thinks of a caring figure who, though flawed, knows what is beneficial for his children and attends to their requests. Such a notion must be at least some credit to poor Joseph, for when he recalls the figure of a father, Jesus furnishes it with details intimating he is making use of his memories.

What have we proven with certainty? Very little. The benefit of this exercise is reading Christ’s life as a whole, his adulthood with his boyhood; to recall that the man Jesus did not burst onto the scene ex nihilo, but behind his appearance in Galilee is three decades of biography; and that somewhere in that biography is a father who shared the bread from the sweat of his brow with the Bread of Life and called him son decades before others called him Lord.

Joseph of Nazareth’s key role in the gospel drama is to adopt the child of Mary as his own and thus secure him in the line of David. However, Joseph’s paternal love not only fulfilled Old Testament prophecy (see Mic. 5:2), but may also have shaped the teachings of Christ.

***

Dedicated to Brian Adams. Happy Father’s Day!

Footnotes

For an overview of Joseph’s role and significance in the Gospels, see Blake Adams, “Meet Jesus’s Other Father: The Overlooked Legacy of Joseph of Nazareth,” Word by Word, Logos (blog), March 19, 2025. https://www.logos.com/grow/nook-joseph-father-jesus/.

BackSee Mike Aquilina, St. Joseph and His World (Scepter, 2020), ch. 8, for a conversation about what Joseph would have taught Jesus regarding Jewish cultic practices, particularly Passover.

BackMaximus the Confessor, The Life of the Virgin, trans. Stephen J. Shoemaker (Yale University Press, 2012), 43.

BackEdward Schilebeeckx, Mary, Mother of the Redemption, trans. N.D. Smith (Sheed & Ward, 1964), 144–45.

BackSo argued by Aaron Milavek, The Didache: Faith, Hope, and Life of the Earliest Christian Communities, 50–70 C.E. (Newman Press, 2003), 82–86.

BackFor an overview of Greco-Roman and Jewish fatherhood, see Diane G. Chen, God as Father in Luke–Acts, Studies in Biblical Literature 92 (Peter Lang, 2006), chs. 2–3.

BackJesus uses the same foil device in the parable of the persistent widow: If even an unjust judge can be swayed by persistence pleas to dole out justice, how much more a just and divine Judge (Luke 18:1–8).

BackSee Adams, “Meet Jesus’s Other Father," https://www.logos.com/grow/nook-joseph-father-jesus/.

Back